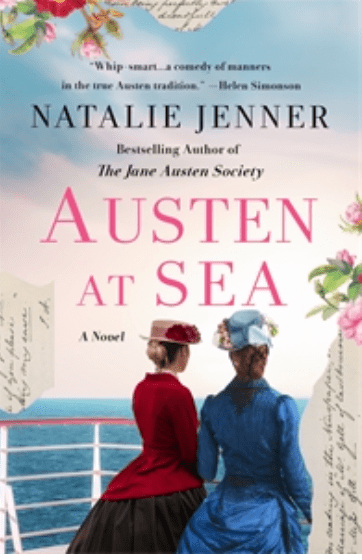

An enthusiastic five stars for this marvelously fulfilling piece of historical fiction. The story manages to be both intellectually rich and emotionally pleasing. My perfect blend! In 1865, two daughters of the long-widowed Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice pen a daring request to the only surviving brother of their favorite author — Jane Austen. Meanwhile, two Philadelphia book collectors have similarly engaged with Admiral Austen about Austen memorabilia and editions. On the side, the Justices of the Massachusetts Supreme Court have elected to read and discuss the entire Austen oeuvre over the very summer break that sees the four correspondents heading off to England. Their discussions are completely engrossing, putting into dialog multiple well crafted opinions and surprising me with their depth. The story itself takes the reader from Boston, across to the sea to Hampshire, and concludes with a courtroom drama spectacular spanning both countries.

On the surface, this could pleasurably be read as an engaging comedy of manners a la Austen herself, with the delightful development of surprising relationships etc. But under the tip of the romantic iceberg lies the depth, thoroughness, and insight of the literary, political, legal, and economic contexts of the time period. Equality, justice, freedom — these are topics on everyone’s tongues during the post-Civil War recovery period, the still relative newness of the United States, and the current battles in both locations for various forms of women’s rights (including, but not limited to, women’s suffrage). These issues are brought out with a number of different techniques. Those discussing Austen’s works have literary discussions about her characters, their roles, purposes, desires, and life lessons. Women’s rights are addressed (and argued) through a fascinating panoply of laws, Acts, and jurisdictions — exemplified by the situations and experiences of the various characters. It’s obvious to us today (I hope!) that women should have rights equal to those of men, but to hear the completely sensical arguments and rebuttals on both sides of the issue during that time period by people who were not inherently “evil,” was deeply interesting.

I both read and listened to this book. I actually preferred the audio in this case. It slowed me down enough to actually listen to different viewpoints and consider them carefully — I usually read too fast and often miss important details. Rupert Graves is the reader — a wonderful actor with a beautiful reading voice. I learned a lot about Austen’s life and her works (despite the fact that I’ve read each multiple times) and enjoyed a wide array of references from that time period — including Louisa May Alcott who appeared in a delightful cameo role. The cast of characters at the start of the book is quite helpful.

Highly recommended.

Thank you to St. Martin’s Press, Macmillan Audio, and NetGalley for providing an advance copy of this book in exchange for my honest review. The book will be published on May 6th, 2025.